Comment

No easy fix: new household projections bring home the urgent need for a fundamental rethink of the standard method

Thankfully, yesterday’s release of 2018-based household projections brings none of the chaos which followed that of the 2016-based dataset, which essentially broke a standard method that had then been in place for a matter of months. Reverting to the 2014-based projections was the favoured short-term solution, giving time to develop and introduce a new approach ‘by the time the next projections are issued’.

While much has changed in the intervening twenty months, it is disappointing and frustrating – if not surprising – that yesterday’s deadline was missed. A resolution to this protracted issue does not appear to be imminent, with Housing Minister Christopher Pincher having last week warned that it will be ‘months rather than weeks’ before a new method would be published. Add an expected period of consultation, and without decisive and long overdue action the present uncertainty could linger for much of what is left of 2020. This is unfortunate and could have been avoided.

To be clear, the release of the 2018-based projections changes nothing as things stand. The existing guidance is unequivocal that the 2014-based projections must be used to set the baseline for the standard method, and this will presumably remain the case until the guidance – and the method – is replaced. It does, however, increasingly feel that any application of the existing method produces local housing need figures that are on borrowed time.

The Government may have held out hope that the household projections would simply fix themselves, with the 2018-based iteration offering a more stable foundation than its predecessor for the purposes of assessing housing needs, but that was never likely to happen. The ONS stood by its approach, while being increasingly open on its limitations, and it is therefore no surprise that the methodology is largely unchanged. It is equally unsurprising, therefore, that the outcome is the same.

The 2018-based projections suggest that around 160,440 households will form annually in England over the next decade, slightly lower than the 2016-based projections (c.165,250) and substantially lower than the 2014-based projections (c.214,130) that currently form the baseline for the standard method. It remains the case that this is simply too low a baseline if the Government is to realise its ambition of delivering 300,000 homes per annum, and it is almost impossible to save it through proportionate uplifts of the kind that currently feature in the standard method. The 2018-based projections would nationally need to be elevated by some 87%, considerably in excess of the 40% cap in the current method. Simply raising or removing the cap however is not the solution to a complex problem, in our view, as this would ignore the more fundamental limitations of using projections which are based on a backward looking snapshot in time.

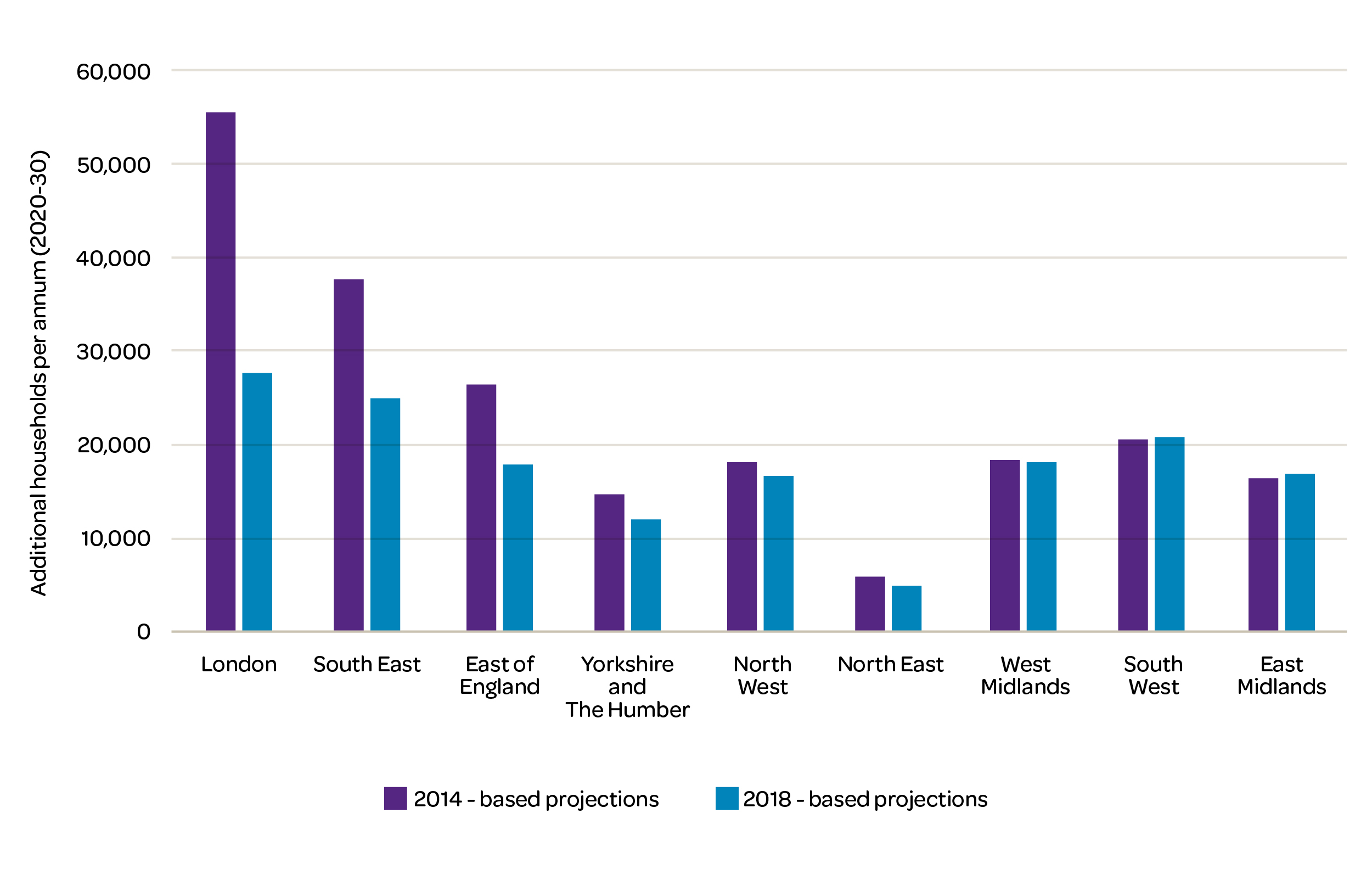

This is clearly illustrated by the fact that the projections have fallen most in the least affordable regions – see Figure 1. The 2018-based projections halve the growth implied for London by the 2014-based dataset. They would need to be uplifted by some 157% to return to the level of need currently implied for the capital by the standard method. Projected growth in the South East and East of England has been similarly downgraded by a third.

Figure 1: Change between 2014-based and 2018-based projections by region

Housing need has not simply evaporated in these areas, or nationally, and the reductions actually flow from the myriad assumptions that have to be made in developing trend-based projections of this nature. In this context, the implications of the recent shift to a two year trend period in terms of migration cannot be ignored without careful consideration.

Given the implicit need to apply assumptions, the ONS is upfront in highlighting that ‘household projections are not a prediction or forecast of how many houses should be built in the future’. It transparently confirms that they take no account of local development aims, policies on growth and the capacity to accommodate population change amongst other factors [1]. Variant projections, published alongside the principal dataset, do not address these shortcomings as the very nature of trend-based projections means that they will never provide a scenario which talks to a national agenda of “levelling up”, where departure from past trends is a prerequisite. The Government cannot wait until such a departure is reflected in trend-based projections, as none are now proposed to be published for at least three years – making it impossible to achieve its December 2023 deadline for national Local Plan coverage.

With such limitations, and from the perspective of planning, it is fair and sensible to ask whether household projections are really the most appropriate bedrock for a standard method of assessing housing need – itself a critical tool informing a new generation of Local Plans that are squarely aimed at addressing a housing crisis which has been decades in the making.

We believe it is time to go back to the building blocks of the method, with an appreciation of its objectives front and centre. Where the limitations of trend-based household projections are accepted, could the existing housing stock of an area act as a more stable foundation, with a minimum rate of growth assumed as a starting point to ensure that each area makes a proportionate contribution towards meeting a national need for more homes? Should further steps be used to expect more from areas with strong economies, to sustainably balance housing with jobs, and those with the most pressing affordability issues?

We believe so. A revised method cannot simply incorporate 2018-based projections. A fresh approach, which addresses the numerous shortcomings of the current method and supports economic recovery across England, is urgently needed and long overdue. It offers the opportunity to provide an immediate positive impetus to plan-making and housing delivery.

Please contact Andrew Lowe or Antony Pollard for more information.

30 June 2020

[1] Household projections in England Quality and Methodology Information (QMI) 29 June 2020