Comment

If it’s broken, fix it: Limitations of new population projections expose the need for a fresh approach to the standard method

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) released new 2018-based sub-national population projections (SNPP) on the 24 of March. These projections usually provide early insight into where local authorities may come under increasing pressure to plan for different levels of housing need, prior to their translation into household projections.

The introduction of the standard method, however, and the subsequent quick and imperfect fix reverting to the 2014-based projections as its baseline means that this dataset could attract less immediate attention. That said, its release in our view reinforces the sentiments increasingly expressed within the planning and development profession that the ongoing use of these trend-based demographic projections as a means of forward planning for the delivery of housing has, for the short-term at least, reached an end.

This is particularly the case in our view owing to:

- The volatile nature of these types of projections. The exposure to only a historic snapshot in time has been further intensified for the 2018-based SNPP by the decision to draw upon a very narrow two year historic period, as opposed to the usual five year trend. Whilst we appreciate that this is driven by methodological improvements in the past two years, this unfortunately means that the projections are at greater risk of being influenced by external factors, not least the number of homes an area has built, during a very narrow window of time that may not be representative of longer term trends.

- The longevity of this specific projection, which will not be replaced for at least three years to allow the findings of the 2021 Census to be taken into account. While there is some logic to this delay, we cannot escape the view that backwards-looking projections are increasingly unlikely to offer useful insight into future trends arising from Brexit as well as the unfolding implications of and recovery from Covid-19.

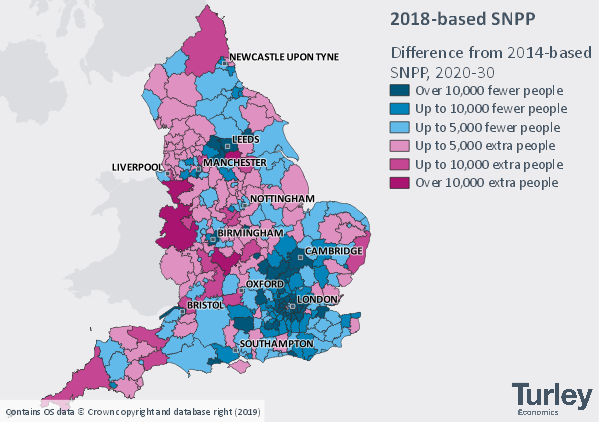

- The spatial pattern of projected growth “thrown up” by the projections, which does not align with the Government’s views on sustainably accommodating and supporting growth across the country. Figure 1 below illustrates for example that large parts of the South – including London and the Oxford to Cambridge Arc – are now projected to see considerably less population growth than implied under the current 2014-based baseline, felt to be most consistent with the Government’s aim of significantly boosting housing supply, despite these being priority areas for infrastructure investment and business support. Equally, whilst a slightly more positive picture emerges in the North and Midlands, the big swings seen in areas such as Birmingham, Greater Manchester and Leeds sit at odds with the Government’s desire to encourage greater housing development within and adjacent to such urban areas [1]. That is not even to mention the apparent conflict with their central role in the Midlands Engine and Northern Powerhouse, so critical to the Government’s “levelling up” agenda.

The ONS is candid about the limitations of its projections, accepting that population change within local authority areas will actually be ‘strongly influenced by local economic development and housing policies’ and emphasising that:

“Population projections can indicate that existing trends and policies are likely to lead to outcomes that are judged undesirable, and if new policies are then introduced, they may result in the original projections not being realised; however, this means the projections will have fulfilled one of their prime functions: to show the consequences of present demographic trends with sufficient notice for any necessary action to be taken”. [2]

The irony of this statement, as anyone trying to plan positively for housing growth and delivery will attest, is that there is no compulsion under the Government’s standard method to develop policy which shifts “present demographic trends” to another trajectory locally – perhaps one which is more sustainable, which enables economies and people to flourish, which drives prosperity and helps to rebalance the economy.

Call for action

The release of this data, regardless of its limitations, puts further pressure on the Government to update its standard method, with its “quick fix” based on data that is increasingly irrelevant and difficult to defend. The limitations documented by the ONS in our view underline the importance of moving beyond the use of such projections for the purpose of long-term planning, and shifting the end goals to future economic resilience, improved prosperity and the provision of homes of the right type, tenure and size to meet the needs of all households. Put simply – the standard method is “broken” and needs to be fixed urgently. The “fresh approach” promised by the Housing Secretary sounds promising, with more detail to follow in the coming months, but must ultimately result in outcomes for local areas that are consistent with the Government’s wider ambitions and manifesto promises.

Please contact Andrew Lowe or Antony Pollard if you would like to understand the implications of the new projections for specific areas of interest, or wish to discuss the consequences of an evolving standard method.

25 March 2020

[1] MHCLG (2020) Planning for the Future

[2] ONS (2020) Subnational population projections quality and methodology information